Tiny Fish

Hello. I’m Jay Owens, a writer and researcher from London, and author of Dust: The Modern World in a Trillion Particles (2023).

That book was born out of this email newsletter, Disturbances, which you most likely signed up to in its previous life on Tinyletter (RIP). I have ported my email list over on to Ghost, from where I now write – but it has been a while since I've last written (July 2023!) and you are of course free to unsubscribe if you no longer wish to hear from me.

Since we last spoke, some things have happened. DUST came out in the UK (Hodder, Aug 2023) and the US (Abrams, Nov 2023) and got reviewed better and more widely than I could ever have hoped, including Nature, ‘book of the week’ in the Sunday Times, 3,000 words in the New York Review of Books and a Long Reads excerpt in the Guardian. My favourite podcast was with Chal Ravens on Novara FM, when we went long on the murderous politics of tiny particles. I know James C. Scott read it and recommended it before he died.

A trillion thanks to everybody who bought a copy or borrowed one from the library. I knew I was on to something with dust, but I didn’t expect this.

If you would like to buy a copy, I suggest the UK paperback edition, which fixes a number of copyediting errors (I am so sorry about those) and can be imported into the US fairly inexpensively from the UK.

Buy from Bookshop.org to support independent bookshops, London Review Bookshop with a note if you’d like me to sign it (I now work at the affiliated magazine), or Waterstones, Foyles or Amazon.co.uk.

The US cover (by Eli Mock) is an evocative one, though. This edition, in hardback only, is similarly available from local American bookshops, Bookshop.org, Barnes & Noble or Amazon.com.

If you wanted to leave a review on any of these platforms, that would be very kind.

But onward.

It has taken me until recently – and another trip back to the desert southwest of America over the new year – to start writing again.

I don’t know where I'm going next, but that’s why I’ve restarted this newsletter: to once again have a space to find out. The same concerns that animated DUST still haunt me now – the desert landscapes; the conflicts between progress and conservation, cities and hinterlands, colonies and metropoles. I still seek out the grey areas, the ironies and inversions, uncertainties and the unknowable. I write to figure out what I think, and I don’t always get to an answer. Then as now, I promise essays ‘at god knows what frequency’. I hope some of you will stay with me.

Below is a piece first published on the London Review of Books blog as ‘Critically Endangered’ (5 Feb 2025). Thank you to Thomas Jones for editing and for permitting me to repost the piece here. I have slightly extended it to recapture some of the complications, which are, after all, the interesting bits.

* * *

January’s fires in Los Angeles were some of the most destructive in California history. The Eaton, Palisades and Hughes fires burned over 47,000 acres, killing 28 people and destroying more than 16,000 structures. Wildfire experts urge caution over whether the city should ever rebuild in places that are certain to burn again.

According to Donald Trump, the LA fires can be blamed on ‘an essentially worthless fish called a smelt’, which lives in the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta in Northern California. On Truth Social, Trump accused California’s governor, Gavin Newsom, of having ‘refused to sign the water restoration declaration put before him that would have allowed millions of gallons of water, from excess rain and snow melt from the north, to flow daily into many parts of California, including the areas that are currently burning in a virtually apocalyptic way.’

This was not true. ‘There is no such document as the water restoration declaration,’ Newsom’s office responded. ‘That is pure fiction.’ Los Angeles takes most of its water not from the delta but from the Owens Valley (Payahuunadü, the ‘land of flowing water’), the Colorado River and from groundwater.

It is true, though, that Trump, in his first presidency, called for more water transfers in California, and Newsom blocked them. What was at stake was never water for Los Angeles, but for California’s Central Valley, which produces up to 18 per cent of US agricultural output by value: grapes, oranges and tomatoes; dairy; a plethora of nuts. It’s industrialised, financialised Big Ag, fuelled by hydrological engineering at a vast scale: 8.6 km3 of water is delivered through the canals of the Central Valley Project each year, most of it coming from the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers. But two periods of drought between 2007 and 2016 meant farmers had to withdraw hundreds of thousands of acres from cultivation.

In February 2020, Trump spoke at a rally in Bakersfield to announce billions of dollars to repair and extend water infrastructure in the Central Valley. ‘All the farmland will be green and beautiful,’ he told the crowd. So when Newsom announced he would file a lawsuit to stop the president’s initiative in order to protect the ‘highly imperilled’ smelt and other delta fish, Trump wasn’t best pleased.

The delta smelt was at the time functionally extinct: since 2016, surveys in the estuary had failed to find a single fish (though captive breeding populations exist, and have since been released back into the delta). They are delicate creatures. According to Katherine Sun, who works for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, smelt are ‘relatively weak swimmers’ and have to be transported in round containers because otherwise they ‘get stuck in corners, they get stressed out, and they die’. Their numbers started to decline in the mid-20th century as water in the delta became polluted by farm run-off, and billions of gallons were pumped out to supply farms and cities, changing the salinity. Invasive clams ate their lunch. The population collapsed and in 1993 the fish was listed as ‘threatened’ under the US Endangered Species Act as well as California’s own ESA. In 2009, the state upgraded the delta smelt’s status to ‘endangered’.

The 1973 Endangered Species Act is arguably the strongest piece of environmental legislation in the world. A recent study estimated that 291 species would have disappeared were it not for ESA protections, and 99 per cent of species listed on it have survived. One of its requirements is that that ‘any action authorised, funded or carried out’ by a federal agency ‘is not likely to jeopardise the continued existence’ of an endangered or threatened species, or ‘destroy or adversely modify’ the ‘critical habitat’ essential to its survival.

As a result, a tiny fish can stop billions of gallons of water transfers, impact billions of dollars of Central Valley farming, and earn the enmity of the United States president.

Trump is not the only Republican to denigrate the delta smelt. In 2010, the California congressman Tom McClintock spoke out against ‘the wilful destruction of 500,000 acres of American farmland by these massive water diversions, all for the enjoyment and amusement of the three-inch-long delta smelt’. In 2011, Sarah Palin blamed the smelt’s habitat protections for taking away the ‘lifeline’ of Central Valley farmers. ‘Where I come from,’ she said, ‘a three-inch fish, we call that bait.’ David Bernhardt worked as a lobbyist for the farmers until shortly before he joined the first Trump administration as secretary of the interior. Under his jurisdiction, the US Fish and Wildlife Service released a ‘biological opinion’ that pumping water from the delta would not harm the fish. Scientists were outraged, citrus growers jubilant. Lawsuits followed.

In December I tried to see another endangered fish, the Devils Hole pupfish. These silvery iridescent creatures live in a single cave just 22 metres long and 3.5 metres wide, surrounded by the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, Nevada. The species has been completely isolated since the end of the last Ice Age, between ten and twenty thousand years ago, when the great lake that filled Death Valley receded, fragmenting pupfish populations into separate ecological niches. Devils Hole is thought to be ‘the smallest habitat in the world containing the entire population of a vertebrate species’, and its pupfish may be the most inbred species in the world: any two individuals are on average 58 per cent genetically identical, moreso than siblings.

A superlative fish, then – but one that almost vanished. People had been partying with the pupfish, a woman at the visitor centre told me: they’d climb down to the cave and sit in the warm 93°F water, drinking beers. In 2013, the pupfish population dropped to just 35 individuals, and the entrance to the cave has since been fenced off. There is a viewing tunnel of sorts, but from twenty metres away, in a dark pool, the inch-long fish are nowhere to be seen.

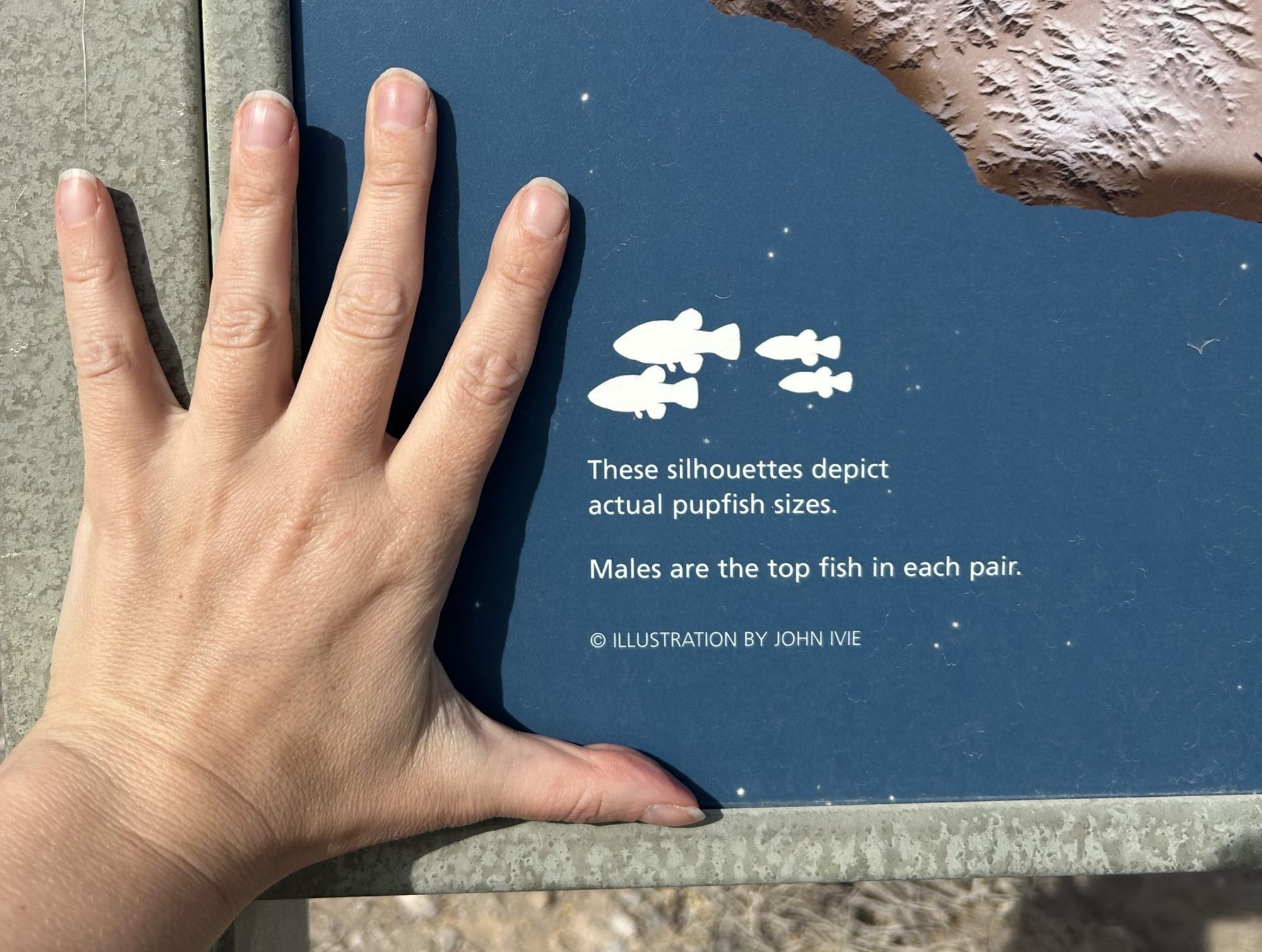

1. Devils hole pupfish in the captive breeding program (Ryan Hagerty, digitalmedia.fws.gov) 2. I told you they were small

1. Fenced-in fishes at Ash Meadows National Wildlife Reserve, Nevada. 2. The entire habitat of the Devils Hole pupfish (both pictures mine)

In order to see a pupfish, I would have to visit another species. Fortunately there are several, including the Warm Springs pupfish (endangered), the Cottonball Marsh pupfish (threatened) and the Owens Valley pupfish (spared from extinction by one man with two buckets on an August afternoon in 1969). The Ash Meadows Amargosa pupfish was however the most convenient, living just a couple of miles away in Crystal Spring.

Ash Meadows, ‘the Galapagos of the Mojave Desert’, provides habitat for 26 plants and animals found nowhere else in the world. Its wetlands are fed by fossil water more than ten thousand years old, which comes to the surface in over thirty seeps and springs. Yet in December 2024 it was bone dry. Winter is the rainy season in Southern California and the Mojave, but this winter the rains didn’t come. Los Angeles saw only 0.06 inches between July 2024 and early January, its second driest period in almost 150 years.

At Crystal Spring, a couple of miles from Devils Hole, the alkali meadows were dried to a crisp and invasive tamarisk trees sprawled grey-brown over the boardwalk. Yet the springs were beautiful, the water bright turquoise from dissolved minerals. And in a small, clear stream flowing through reeds, three Ash Meadows Amargosa pupfish were swimming against the current. A sign on the boardwalk described them as ‘playful’; they’re called pupfish because they reminded the ichthyologist Carl L. Hubbs of puppies. I wanted to give them a tickle, but figured I probably shouldn’t.

The Devils Hole pupfish was among the first species to be listed under the 1967 Endangered Species Act (it is now ‘critically endangered’), and in 1976 the US Supreme Court established minimum water levels at Devils Hole to ensure their survival. At first this was deeply unpopular, as water rules limited groundwater pumping by local ranchers – but in the last two years ‘the narrative is completely flipped’, as Mason Voehl, executive director of the Amargosa Conservancy, told Inside Climate News last year. ‘People are now saying “We’ve always hated the pupfish, but now it’s going to save us.”’

A company named Rover Critical Minerals wants to test Ash Meadows’ potential for lithium mining, yet drilling for samples could contaminate the aquifer. Residents rely on groundwater wells for drinking water, and those wells are already coming up dry. For the Timbisha Shoshone tribe, the water sustains their sacred traditions. For a time, the laws defending the pupfish seemed to offer the best chance of protecting people’s water, too. On 14 January, the outgoing secretary of the interior, Deb Haaland, issued a ‘mineral withdrawal’ suspending new mining activity across 309,000 acres of land around Ash Meadows Wildlife Refuge. It seems unlikely that Trump – or Elon Musk – will honour it.

The scope of the Endangered Species Act was defined in the 1970s by a third tiny fish: the snail darter, which lives in the Little Tennessee River. It was the subject of the first ESA lawsuit to reach the Supreme Court: could the snail darter’s right to clean water prevent the construction of the Tellico Dam? The court ruled in 1978 that the ESA explicitly forbade the completion of any infrastructure project that was likely to result in the elimination of a species. Environmental concerns trumped economic development, and a $53 million construction project was stopped (until Congress passed an exemption for the dam the following year). The darters were transplanted to other river systems and in 2022 removed from the endangered species list.

The ESA passed under a Republican president as a bipartisan consensus, 355-4, but in years since it has become highly controversial. As the cases above show, the act enables tiny fish and an array of other microfauna (or the environmental campaign groups acting on their behalf) to stand in the way of billions of dollars of capital.

Critics also claim the Endangered Species Act blocks progress and the public good. Elsewhere in Nevada, endangered plant species such as Tiehm’s buckwheat and Amargosa niterwort have been central to legal battles against lithium mines. Is a rare plant reason enough to prevent renewal energy development? Not only Republicans are sceptical. ‘We’ve got to meet the moment on climate change,’ Laura Daniel-Davis, acting deputy secretary of the interior under Biden, told the New York Times, ‘and public lands have to play a foundational role.’ Seaver Wang of the ecomodernist Breakthrough Institute argues that ‘our perspective needs to be holistic. Blocking a project might prevent impacts on a species ... but it may cause a slower energy transition + push projects elsewhere with higher impacts on communities + ecosystems.’ Yet for many conservationists, every endangered species must be protected. As Patrick Donnelly of the Center for Biodiversity puts it, ‘the integrity of the Endangered Species Act is at stake.’ If one species is allowed to ‘go extinct for lithium’, he says, ‘it puts all endangered species at risk.’

We ask a lot of some very small fish. Single species are relied on to save entire ecosystems. Last month, researchers at Yale announced that the snail darter is not a distinct species at all: it is genetically and physically identical to the stargazing darter, a fish plentiful in US waters. The species identification may have been driven by a desire to stop the dam, a temptation taxonomists recognise as the ‘conservation species concept’.

Might emerging ‘rights of nature’ legal models allow for more holistic environmental protection by allowing natural entities such as rivers to have legal protections, even legal personhood?

In the US, at least, the question may now be moot. Among the barrage of executive orders Trump signed on his first day in office was a declaration of a ‘national energy emergency’. It calls for ‘the integrity and expansion of our nation’s energy infrastructure’ and reanimates the rarely convened Endangered Species Committee, aka the ‘god squad’ of high-ranking federal officials able to grant ESA exemptions. On Sunday, 26 January, Trump signed a further executive order directing federal agencies to deliver more water through the Central Valley Project and ‘override existing activities that unduly burden efforts to maximise water deliveries’ – getting his revenge on the delta smelt.

Thanks for reading.

I also wrote for the LRB blog in February 2024 about Hell’s Kitchen, and why California’s Imperial Valley ‘cannot be a sacrifice zone for the clean energy revolution’.

I am on Instagram as @hautepop and Bluesky as @jayowens.bsky.social. My web presence is jayowens.me.

I will write again when I next have something to say.